Algeria

ALGERIA

Methods of capture and use of flash floods in the M'Zab valley

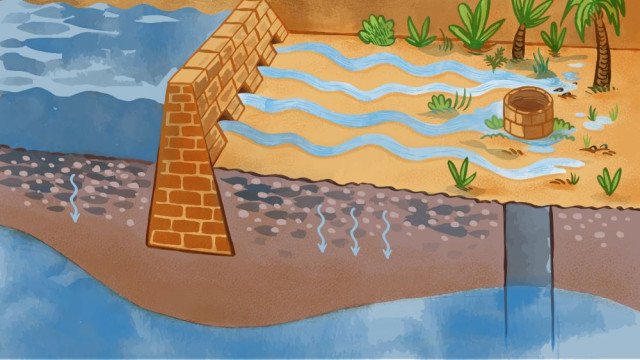

Desert oases represent highly productive anthropic ecosystems built by communities. Thanks to participatory methods of natural resource management, they manage to thrive through intensive agriculture with high added value. In such arid environments, water conservation from irregular rainfall and flash floods is crucial to establishing human settlements.

The M'Zab valley lies in the heart of the Sahara and is home to five ksours (fortified villages), founded between 1012 and 1350 AD. Over centuries, local communities have ingeniously preserved groundwater through a combination of small dams and infiltrating trenches that collect the water from flash floods.

These ingenious geoengineering techniques not only allow water capture but also preserve fertile soil - unlike recently introduced intensive agriculture which makes unsustainable use of aquifers.

Copyright: A. Saidani

and M. Hamamouche,

UMR G-Eau and CIRAD

(Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement).

Drawings: Laura Micieli

From left to right (above):

1 - Aerial view of the M’Zab Valley, where the ancient Saharan oasis of Beni Isguen, founded in the 14th century, is located. For centuries, ingenious water-management techniques have harnessed the seasonal floods of the usually dry riverbed (wadi) transforming the arid landscape into a flourishing oasis with cultivated fields and palm groves.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.

2 – At the entrance to the palm grove, diverted floodwater is channeled into a shared space. Originally constructed by the first inhabitants of the M’Zab Valley, this hydraulic structure serves to regulate and fairly distribute the precious water flow through a network of canals.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.

3 - A system of small dams and infiltration trenches captures the waters of the flash floods. This ancient technology slows the flow and guides water into underground aquifers—a natural storage system that preserves it for irrigation throughout the long, dry months.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.

4 - The traditional irrigation system is a sophisticated blend of surface and groundwater flows. Water is conveyed through earthen channels called seguiat, whose width is carefully proportional to the volume of water they are designed to carry. While this ancient network remains functional, many smaller seguiat have now been replaced by modern PVC pipes.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.

From left to right (below):

5 – Mint is cultivated using a modern drip irrigation system. This method delivers water and nutrients directly to the plant roots with remarkable efficiency, minimizing waste and maximizing yield. It’s a blend of contemporary agricultural technology with the oasis's enduring spirit of water conservation.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.

6 – The Charoun is the most important groundwater recharge well in the system. Engineered with significant capacity, it can absorb vast quantities of floodwater. This process directly replenishes the aquifer, which in turn supplies the surrounding network of irrigation wells, ensuring water security for the entire community.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.

7 – After an extended drought, community members clean a dried-up irrigation well. This labor-intensive maintenance is a crucial, recurring task to remove silt and debris, restoring the well's capacity to draw groundwater and renew the flow of life to the oasis fields.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.

8 – A submersible pump, connected to the electrical grid, draws groundwater from the depths of an irrigation well. This modern technology provides a reliable supply for local agriculture demonstrating the ongoing adaptation of the oasis's ancient systems.

© M. Khouadja, M.A. Saidani, M.F. Hamamouche, UMR G-Eau & CIRAD.